The BMA has published its Safe Working in General Practice Guidance, which is in effect its guide to collective action. It does not appear to be full of any major surprises, and rather provides practical guidance for practices on how they can implement the changes that they have already described. However, it includes a section on the PCN DES, which raises the question of whether it would be better for practices to leave the PCN DES altogether.

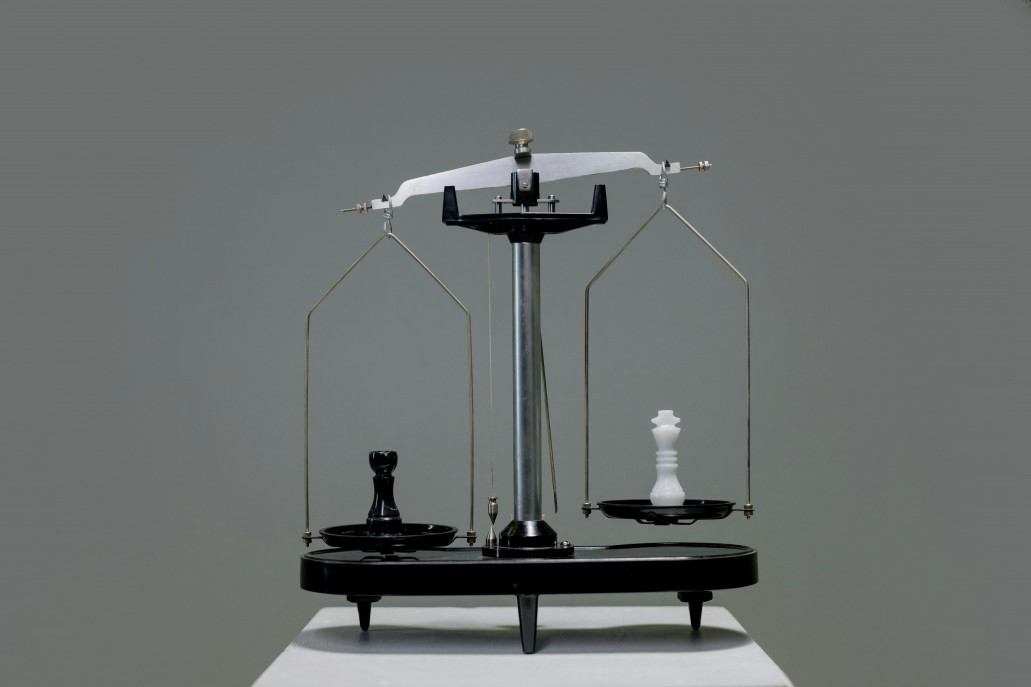

To be clear, the guidance does not come out and outright say that practices should leave the PCN DES. Instead it is implied. It states, “Many feel that the requirements of the DES outweighed the benefit brought by the investment into practices and ARRS (Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme) staff.” It then states, “Practices will need to consider if the PCN DES enables them to offer safe and effective patient care within the context of their wider practice and their present workforce” before going on to outline the mechanism by which practices can choose to opt out.

“Many” is a vague term. It implies the majority of people, but it can simply mean a large but indefinite number. If it was true that the majority really thought the requirements of the DES outweighed the benefits the current sign up rate to the PCN DES would not be over 99%. Many dislike the requirements of the DES, but that is not the same as considering that their practice would be better off financially by not being part of it.

The problem of leaving the PCN DES is not just about losing the resources (both the financial income streams and the ARRS staff). It would also mean GP practices ceding control of the PCN and these staff. As the BMA guidance points out, ICSs are obliged to continue to provide PCN services to practice populations, and so the most likely scenario in the event of general practice refusing to take this on is a neighbouring PCN or another provider such as a community or acute trust taking the PCN on.

Strategically, this would be a terrible outcome for local general practice. While the BMA sees a very clear distinction between investment in core general practice and overall primary care funding (i.e. including PCN funding and other non-core general practice funding), the government do not. The government has committed to increasing the percentage share of NHS funding that primary care receives, but if general practice loses control of PCN resources it could end up receiving very little if the additional funding comes through that channel.

The BMA don’t believe that another provider would be able to take on the PCN responsibilities if practices withdrew. But ultimately it is not their livelihoods that they are gambling with if they are wrong. The BMA wants the funding that goes into PCNs to be shifted to core contracts. But national policy is firmly against this, and so practices that resign from the DES will be taking a huge personal risk that this is what will happen when the likelihood is that it will not. There are clearly divisions within general practice as to the value of PCNs, and so there is not going to be a mass resignation from PCNs, meaning those that do leave are going to be very exposed.

At present, practices can work with their PCN to find mutually beneficial ways of ensuring PCN requirements are managed alongside supporting practice sustainability, both through direct financial flows and through PCN services like pharmacists and home visiting teams that support practice work. But if ties were to be severed, then this link and these opportunities would be lost, and practices in a far worse position than they are now.

NHSE and the government like PCNs, which is why from the BMA perspective resignations from the PCN DES are desirable as a leverage for negotiation. But the risk to those that take such a step, when the BMA have not come out and explicitly said that this is what they want, is extremely high. Rather than leaving altogether and losing the opportunity to access the existing and (potentially larger) future resources, it would seem a much more sensible stance for practices to stay within the PCN, keep control, and campaign to be able to access more of the PCN resources in future.