The NHS mantra that bigger is better and that the best thing for general practice is for it to grow in size is one that mostly goes unchallenged. Surely it is obvious that if we want to join up care around the needs of the patient then it can’t possibly make sense for there to be 6500 individual practices, as this is far too many for the NHS to sensibly do business with. But what if the issue is that the NHS is too big, not that general practice is too small?

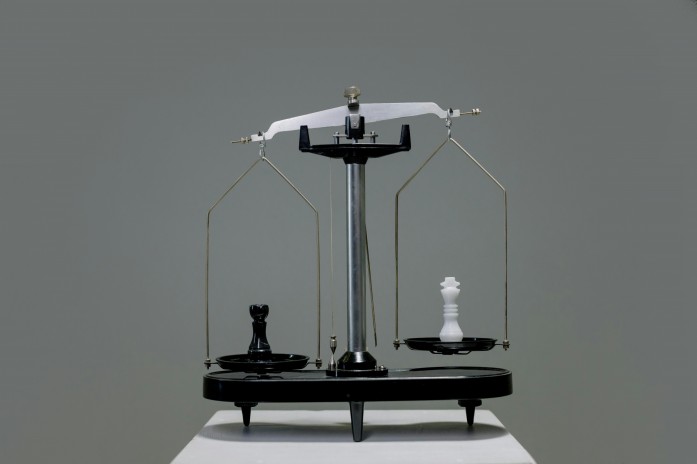

Most of us are familiar with the concept of ‘economies of scale’. These are the cost advantages organisations can gain from increasing their size, which come from both spreading the fixed costs such as management, accounts, HR and IT more widely (and so for general practice result in less of the £ per patient received being spent on them), and from reducing the variable costs by enabling a greater skill mix, more specialisation, more investment in IT and lower procurement costs (so that actual cost to the practice per patient can be reduced).

However, it is does not follow that the greater the size the lower the costs. What happens is that another concept – ‘diseconomies of scale’ – kicks in. Diseconomies of scale happen when a company grows so large that the costs per unit (in our case per patient) actually increase.

Costs grow with size for a number of reasons. Practices become too large to be properly coordinated, which in turn creates more work and issues than when everyone knew everything that was happening. Diseconomies of scale also occur because of the difficulties of managing a larger workforce. Communication is less effective, staff don’t feel listened to and don’t feel part of the organisation, and this in turn affects productivity.

The biggest issue with scale in the NHS is the distance it creates between those delivering front line care and those making decisions about the organisation. In GP practices the partners for the most part also work on the front line delivering direct patient care. They understand the challenges, and the decisions they make are intended to resolve them.

Once a practice covers multiple different sites then a distance is created between the challenges at any individual practice and the decision making of those in charge. When this distance becomes too great, diseconomies of scale can kick in.

Think how hard it is for a PCN CD to manage the needs of each of the member practices and meet the requirements of the PCN DES. For NHS organisations this issue is magnified. Not only are the leaders a huge distance from the front line of care delivery (consider the executive offices running a group of NHS hospitals, as is increasingly becoming the NHS norm), the motivation behind decision making is distorted from improving the delivery of frontline care. Instead, it is replaced with an upward-looking agenda, seeking to meet the wishes of regional and national NHS leaders and politicians.

Operating as a single, national, political NHS creates huge diseconomies of scale as external pressures consistently pull against local decision making made in the local interest. The only part of the NHS that has been able to resist this and operate effectively and efficiently for its own patients is general practice.

The integration agenda assumption that what general practices needs is to be bigger and a more formal part of the NHS in order to join up care around the patient is one that needs to be seriously challenged. Real integration requires decision making by those with a direct understanding of local needs, and the existing model of general practice is far more suited to that than the way the rest of the NHS operates.

1 Comment

How I agree with this! Identification and recognition of local needs is key to success in improving health outcomes for patients, particularly in primary care. One size really doesn’t fit all. Even within a single PCN, the disparity in deprivation and social needs which impact on health can be startling.

However, I do believe that we need economies of scale and that the reason Trusts are such unwieldy beasts is not because they are large, but because they work within and across borders in such an irregular and disjointed way. Different systems, different methods of communicating – and still too much paper!