I am tired. It has been difficult over the last few months not only having to keep up with the pace of change, but also having to constantly adapt and get used to new ways of working. It is not only our professional lives, but our personal lives as well. Everything we do has been completely changed. It has been exhausting.

I know I am not alone. Everyone working in general practice has had their world turned upside down. All we want is some respite.

The talk nationally is of recovery and restoration. Sounds like exactly what we need. But of course it is not about us. It is about restoring the services that are not being offered, and creating that dreadful term “a new normal”.

It is into this context that we hear about how this is a new future for general practice, how we must build on the changes and go further, faster.

But we are tired.

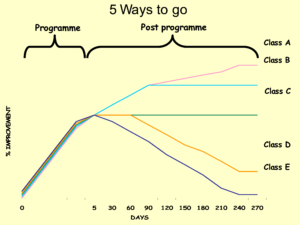

It may be the start of a new future for general practice. Or it may be that many GPs are just waiting for the opportunity to close the much-touted new digital front door. The draw of the comfort of ways of working that we know and trust may well take many back to how things were, not forwards to the newly glimpsed but (for some) highly uncomfortable ways of working we are now experiencing.

Recovery and restoration in general practice needs to start with practices and practice staff. It needs to be about creating time for teams to reflect on the changes they have made over the last few months, to share the things that been difficult and to ask for help where it is needed. We need the opportunity to talk to others about what they have done, how they have coped with the changes, and what the impact has been for them. We want to learn from what they did differently and understand what this teaches us about our own experiences as well as theirs. We need the comfort of knowing we are not the only ones who have found this difficult, and the reassurance that what we are doing now is ok.

We need time to consider whether any of the changes have been positive, and if they have which ones we want to keep. We need the opportunity to think this through for ourselves, rather than be told it by other people. We need to do this at our own pace.

At this point in our covid journey, I don’t think there is anything more important than creating time and space for reflection and review. We have to recognise that we and those around us are tired, that change is difficult and this feels like it has been going on for a long time. We need to create the opportunity for ourselves and our teams to be able to move forward. It may feel counter intuitive, but the way to do this is by creating the time and space for our teams to look backwards, so that we can decide for ourselves where we go from here.