With the vast majority of Practices now a part of a Primary Care Network, and a week into the formal ‘Go Live’ date for PCNs to start operating, PCN Clinical Directors and their teams are starting to consider recruiting the Social Prescribers for whom the NHS are providing full funding in the current financial year. Now is perhaps therefore an opportune time to review the ways in which PCNs can best recruit, train and introduce Social Prescribing to their new organisations.

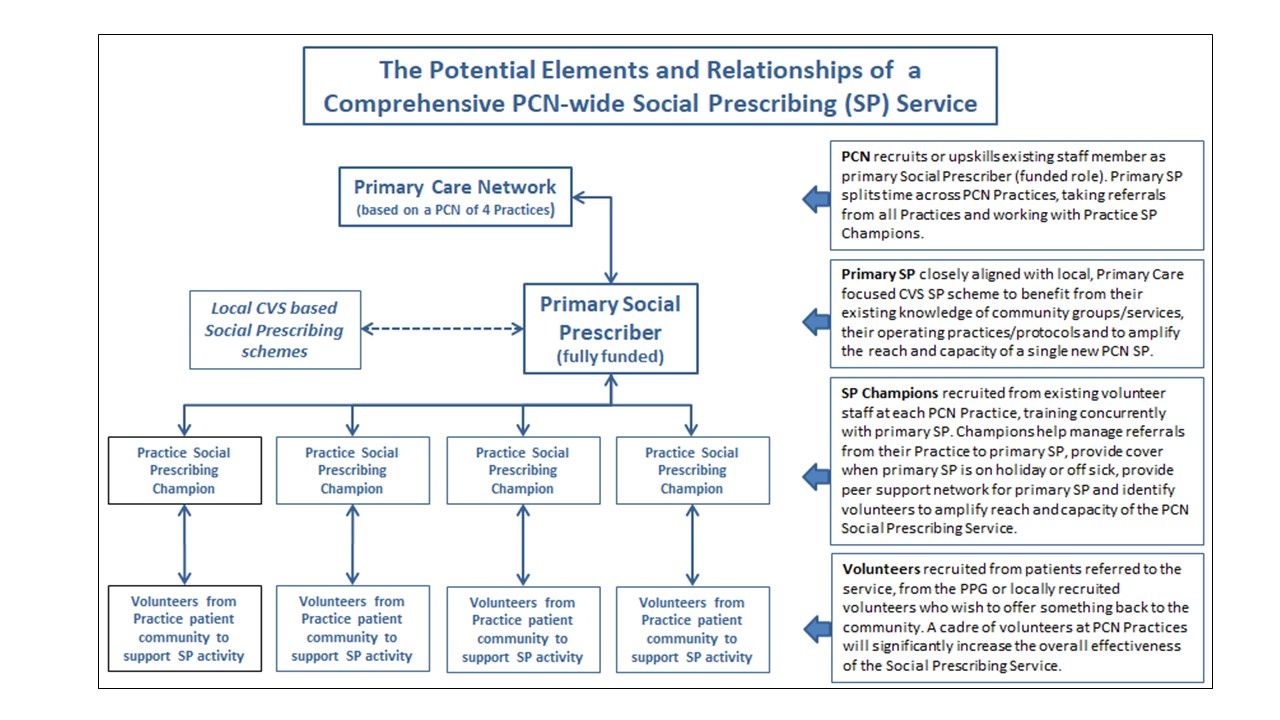

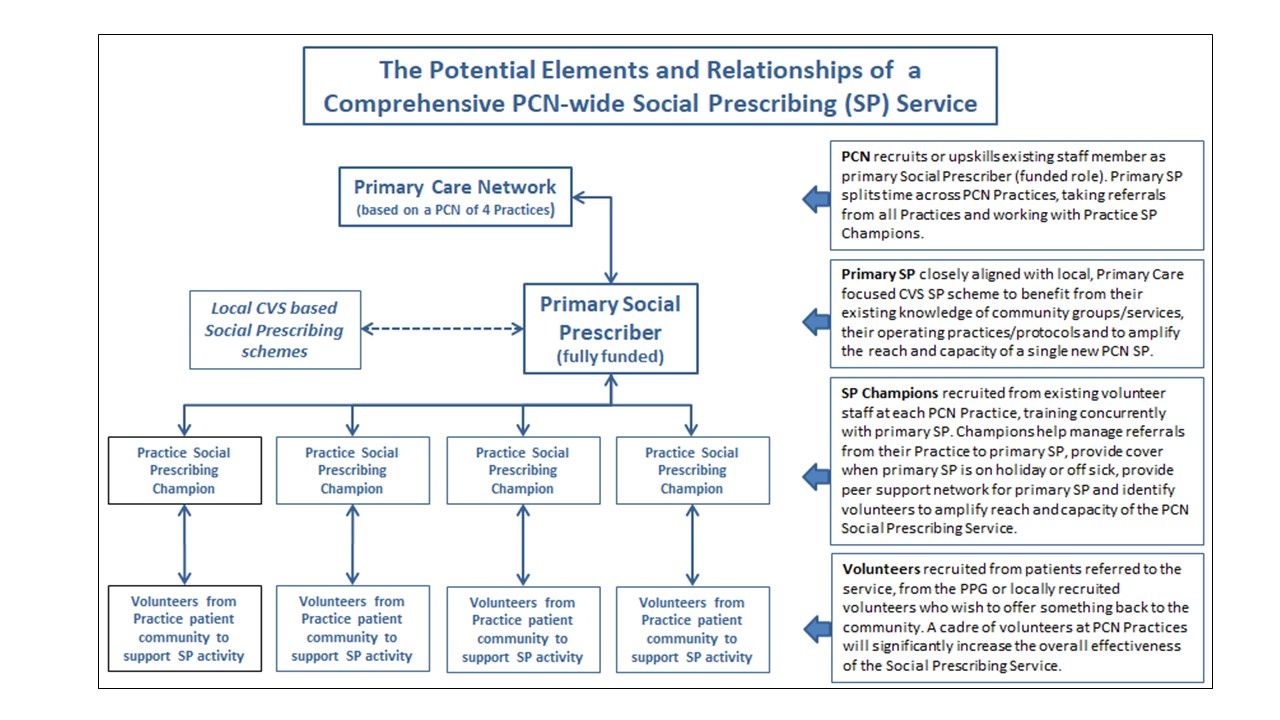

Our engagement with PCNs regarding training for Social Prescribers has identified a number of different models currently being considered by PCNs. Perhaps the most innovative approach is to realise that the opportunity is significantly greater than simply recruiting an additional member of staff. These PCNs are already examining ways in which the recruitment of the new Social Prescriber can herald the introduction of a Social Prescribing culture and the provision of a comprehensive Social Prescribing Service throughout the PCN. This can be achieved by leveraging the people skills of the health professionals already working within PCN Practices and recruiting suitable volunteers from the patient community to support the Social Prescriber, who sits at the heart of the new Social Prescribing Service.

Introducing a Sustainable and Comprehensive Social Prescribing Service across the PCN

It may seem a little counter intuitive, if not naïve, to believe that one can create a sustainable and comprehensive SP service with just a single Link Worker to support potentially 50,000 patients. But with imagination and determination it is not impossible. The key is in being prepared to engage and upskill existing staff and leverage them to support the primary Social Prescriber, and in doing so to help the new funded Social Prescriber be as effective in their role as possible.

Practice Social Prescribing Champions

With the average PCN in England likely to comprise between 3 – 6 Practices (based on an average list size of 8,490 in Dec 2018), forward thinking PCNs are seeking to train up not just the primary Social prescriber but a suitable volunteer member of staff with the right people skills from each of the PCN practices. These Social Prescribing Champions in each Practice will facilitate and smooth the referral process to the primary Social Prescriber, actively recruit volunteers from their patient communities to assist the Social Prescribing Service and will be trained and able to stand in for the primary Social Prescriber when he or she is on holiday or off sick.

Where appointment capacity becomes a problem for the primary Social Prescriber, as experience with the introduction of other allied health professionals suggests it will do, these Practice Champions, trained to the same level as the primary Social Prescriber, can undertake their own Social Prescribing, working in their own Practice and with their own patients to alleviate waiting times for the primary Social Prescriber. This may not be practical in every Practice and will depend on the clinical priorities determined by the GPs, but some are starting with a half day a week of Prescribing from their own trained Champion and building up as appropriate. However, if started, this needs to become a long-term commitment with a long notice period, as continuity of Link Worker is fundamental to building the trust and relationship with the patient.

Volunteers

There is much emerging evidence that using volunteers alongside trained Social Prescribers can significantly enhance the scope and reach of a scheme. Volunteers can provide emotional and practical support to service users and have in some cases been further trained as link workers to provide facilitated referrals to some of the community groups within the local area. They come from a wide range of backgrounds; some may be recruited from patients who have been referred to the service and wish to volunteer as part of their social prescription; others may come from the Patient Participation Group and yet more may be locally recruited volunteers with multiple skills and experience of life who wish to offer something back to the community. Recruitment of a cadre of volunteers at PCN Practices will significantly increase the overall effectiveness of the Social Prescribing service.

A Potential Structure Suitable for a PCN to Establish a Comprehensive Social Prescribing Service (Click image to enlarge)

The Primary Social Prescriber – PCN Controlled or Aligned with Existing Local Scheme?

Given the challenges of expecting a single, unsupported Link Worker to make a significant difference in a patient community of up to 50,000, NHS(E) and the Social Prescribing Network have both suggested that the most effective way of managing new PCN Link Workers is to closely align them to an existing Social Prescribing Scheme in the area. This can range from close collaboration and sharing of administration, resources and operating protocols where appropriate, through to fully outsourcing the employment and management of the Social Prescriber to a local CVS scheme.

For both outsourcing the role and for close collaboration, the choice of host CVS based scheme is crucial. Ideally it should be already working with and taking referrals from Primary Care in some respect so that the working practices and administrative processes are similar. For example, whilst a local Social Housing based Social Prescribing scheme might be delivering great results, it is unlikely to be working closely with GP Practices in the manner that will be expected of a PCN based Social Prescriber. The desired synergies from aligning the PCN Social Prescriber with such a scheme are therefore unlikely to be realised.

Recruiting the Social Prescriber – Upskill or Recruit from Outside?

PCNs are currently considering whether to upskill an existing member of staff as a Social Prescriber or recruit from outside. Recruiting skilled and experienced Social Prescribers from existing schemes in the voluntary sector is a possibility, but this does nothing to expand overall Social Prescribing capacity and is likely to lead to ill feeling between Primary Care and existing Social Prescribing schemes. Additionally, in large urban areas with many PCNs seeking to recruit Social Prescribers, the availability of external, currently unemployed candidates is likely to be quickly exhausted.

Up skilling of existing Practice staff has many benefits; they are already known to GPs within the Practice/PCN, they will be familiar with procedures in the Practice and, if their PCN has undertaken Active Signposting training for their Reception teams, they will have a good understanding of the available services and community groups operating in the area. In short, after suitable training in the specific skills needed by a Social Prescriber, they are more likely to be ready to hit the ground running.

The only real prerequisite for upskilling an existing member of staff is that they fulfil the person specification of a Social Prescriber. These soft people skills are inherent in those who make the best Social Prescribers, and it is no surprise that many come to Social Prescribing from the caring professions. These soft people skills include a natural desire to help people and give them time, the ability to listen, empathy, patience, excellent communication and organisation skills, the ability to inspire trust and confidence, and the flexibility, resilience and initiative to work on their own with minimal direction. Nurses, HCAs, some Receptionists, Social workers and voluntary workers often make good Link Workers.

Training the New Social Prescriber and Practice Champions

If recruited directly from a local CVS based scheme working closely with Primary Care, the new Social Prescriber is unlikely to need much additional training. In all other circumstances however, the newly recruited Prescriber will require upskilling in the specific skills used by Social Prescribers. These include Active Listening, Motivational Interviewing, Health Coaching, preparing Care Plans and managing the administrative processes required of the role so that they align with those of the PCN.

Motivational Interviewing skills are particularly important in a Primary Care setting, where the percentage of referred patients who are at the pre-contemplation stage of the change cycle tends to be higher than for service users in CVS based schemes.

If adopting the PCN Social Prescribing service structure suggested above, the training will also need to encompass the Practice Social Prescribing Champions who, by definition, are unlikely to possess any existing Social Prescribing skills. Training the new primary Social Prescriber alongside the volunteer Practice Champions is a wholly positive approach and should be considered the default. It establishes the supportive network and close personal and professional relationships needed for the Social Prescribing service to operate effectively across the PCN.

If looking for external training support, PCNs would be advised to retain a training organisation, such as DNA Insight, who will train the PCN’s Social Prescribers as a single group and who will customise the training to suit the specific needs and operating protocols of the PCN. Facilitated Active Learning Sets, such as those included in DNA Insight’s SocialPrescriberPlus™ programme, help the whole Social Prescribing team to build an enduring and close personal and professional network that can address challenges, identify and build on Best Practice, increase resilience within the team and meet the priorities set by the PCN Clinical Director and the Practices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the additional resource of a fully funded Social Prescriber to work across the PCN is a wholly positive development. On their own however, the challenge of supporting up to 50,000 patients is likely to be overwhelming and the expected benefits may not extend as deeply into the PCN Practices as had been hoped, especially once the Social Prescriber’s list has filled up and waiting times start to become unacceptable.

PCNs can however take an innovative approach to creating a sustainable and effective PCN-wide Social Prescribing Service – by training, utilising and empowering volunteer Practice Social Prescribing Champions to support the primary Social Prescriber. These Champions in turn recruit volunteers from the local/patient community with lived experience, some of whom may have benefited from the service, to provide practical assistance and support to the team, allowing the team to focus on delivering the best possible care to the greatest possible number of patients.

Other Social Prescribing models are of course available and are equally valid. The key outtake is that with initiative, ambition and innovation it is entirely possible to create a comprehensive Social Prescribing Service for a Primary Care Network, despite only having funding for a single Social Prescriber.

Useful Resources and Social Prescribing networks for PCNs and Link Workers

- Twitter Social Prescribing Wednesday – @SocialPresHour – every other Wednesday and hosted/organised by Elemental

- National Association of Link Workers www.connectlink.org Christiana Melam christiana@connectlink.org Professional body representing Social Prescribers/Link Workers with lots of useful resources for Link Workers and those employing them.****************

Nick Sharples is a Director of DNA Insight Ltd, a GP training consultancy specialising in providing advice and training in the High Impact Actions of the GP Forward View. The SocialPrescriberPlus™ programme is designed for new or existing Social Prescribers and Link Workers, whether GP-based or working in the community. For more information please call us on 0800 978 8323 or visit our website at dnainsight.co.uk