There is something difficult, elusive even, about the concept of governance. It should be straightforward. According to the universal fount of all knowledge (Google) the definition of governance is, “the action or manner of governing a state, organisation etc.” Yet somehow in the NHS, governance has drifted into becoming a stick managers wield over clinicians to drive compliance.

Am I overstating it? I am not sure. The first time I really saw evidence of this was when CCGs were first formed. Keen, eager and green, groups of GPs worked together determined to use NHS money to make a difference to local populations. But then these fledgling organisations were subjected to an “authorisation” process, where the focus was on governance and the ability of CCGs to operate as stewards of public money.

Whatever your views on the rights and wrongs of the authorisation process, the result of it was that it sucked the life and spirit out of nearly all of the CCGs. The model constitution, non-executives, multiple committees (etc. etc.) all contrived to create organisations too unwieldy to make any real change happen, to diminish trust between the organisation and its member practices, and to sap any sense of organisational pride or identity.

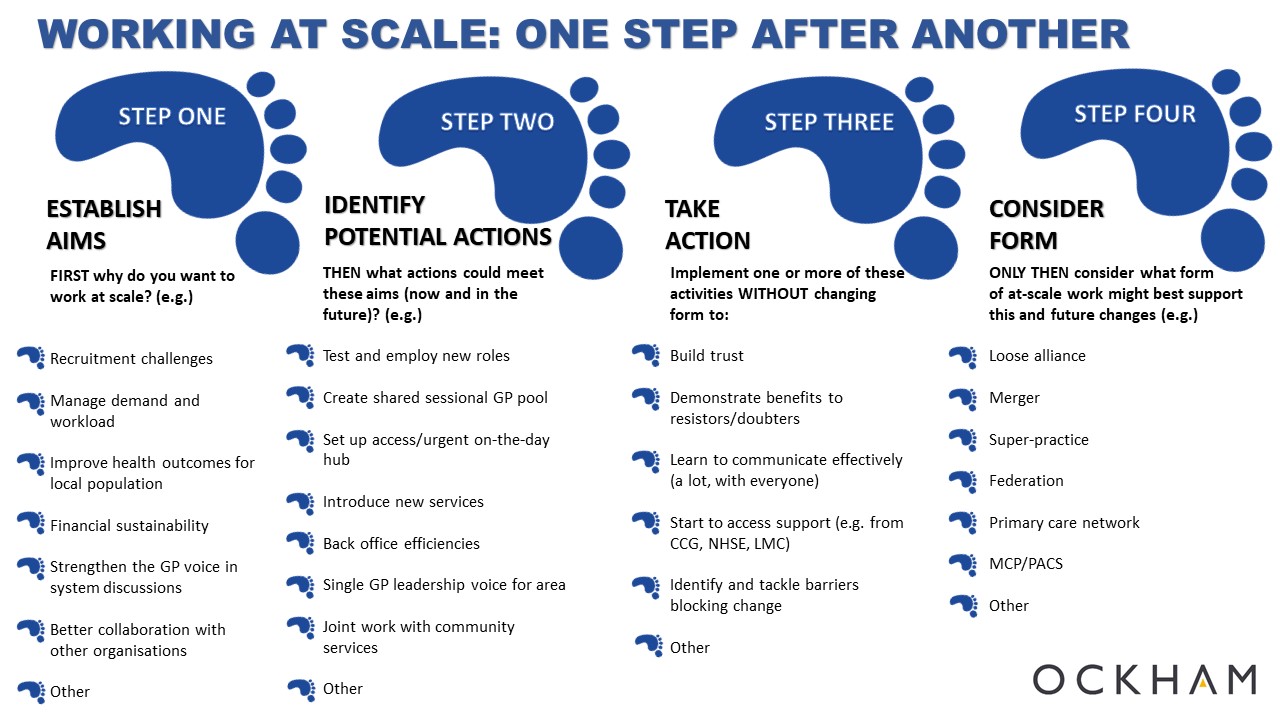

Last week we published our four step guide for practices working at scale. The real point of this was to encourage practices wanting to work at scale to think about why they wanted to work together and what they wanted to do before getting bogged down in questions of governance.

Don’t get me wrong, governance is important. But it is not more important than having a clear purpose for the at-scale general practice organisation, or more important than working out the guiding principles that will determine how the organisation will operate (its values). It is not more important than building trust between the new at-scale entity and the member practices, or more important than achieving the goals the organisation has set itself. Focussing on these things makes good governance an enabler, rather than governance existing for governance’s sake.

In the days when CCGs were being established, the key cry from practices was that it “did not become like the PCT”. Now the concern from practices about the development of new at-scale general practice entities is that they “don’t become like the CCG”. Yet the pressure “to have good governance” is often forcing some of these newly-emerging organisations down the same route. This is the tyranny of governance.

But things can be different this time. The cycle can be broken. At-scale general practice organisations are not statutory bodies in the same way that CCGs are. They do not have to hold population-based budgets (which will take them down the CCG route), and it is perfectly feasible for them to partner with other organisations (with the required governance) to enable that to happen. They can be whatever the member practices want them to be.

This means there is no ‘right’ model of governance for them. There is no checklist they have to adhere to. Appropriate governance will depend on exactly what it is they are trying to achieve and do.

New at-scale GP organisations have choices. First they must determine why they exist, then decide what they want to do and the way they want to do it, and finally choose what governance they need to enable them to do the things they want to do in the way they want to do them. Governance in its place is an amazing enabler, but out of place can create a fast track to failure.