What do you do when your practice reaches crisis point, and it is no longer clear whether the practice can even continue? In this presentation Ben Gowland explores the options open to practices, and identifies the avenues practices can pursue who need to consider radical change.

Much of the narrative around GP demand puts GPs and practices into the role of helpless victim, beaten down by the relentless growth in demand without the resources to meet it. But it is more helpful to focus on the practical actions practices can take to gain control over demand, and attempt to become the hero of their own story.

Demand on GP practices is growing. The King’s Fund 2016 study, Understanding pressures in general practice found,

“Our analysis of 30 million patient contacts from 177 practices found that consultations grew by more than 15 per cent between 2010/11 and 2014/15. The number of face-to-face consultations grew by 13 per cent and telephone consultations by 63 per cent. Over the same period, the GP workforce grew by 4.75 per cent and the practice nurse workforce by 2.85 per cent. Funding for primary care as a share of the NHS overall budget fell every year in our five-year study period, from 8.3 per cent to just over 7.9 per cent.”

Natasha Curry from the Nuffield Trust, in her article Fact or fiction? Demand for GP appointments is driving the crisis in general-practice, examined where the rise in demand for appointments was coming from, and found,

“While activity in general practice has increased, most of that increase is amongst staff groups other than GPs. Consultations with GPs rose by approximately 2 per cent, whereas consultations with nurses rose by 8 per cent and consultations with ‘other’ staff (a long list of professionals including pharmacists, physiotherapists, and speech therapists) grew by 18 per cent.”

Introducing new roles is clearly one mechanism practices have been using to manage the growth in demand. Introducing telephone appointments is another. Both have added to the complexity and challenge of the work the GPs actually do see face to face.

What else can practices do? The NHS Alliance considered “potentially avoidable” appointments in their report Making Time in General Practice. They found,

“Overall, 27% of GP appointments were judged by respondents to have been potentially avoidable, with changes to the system around them. The most common potentially avoidable consultations were amendable to action by the practice, often with the support of the CCG. The biggest three categories were where the patient would have been better served by being directed to someone else in the wider primary care team, either within the practice, in the pharmacy or a so-called ‘wellbeing worker’ (e.g. care navigator, peer coach, health trainer or befriender). Together, these three, which could be improved by more active signposting and new support services, accounted for 16% of GP appointments. An additional 1% were to inform a patient that their test result was normal and no further action was needed. A further 1% of appointments would not have been necessary if continuity of care or a clear management plan had been established.”

I recently discussed how “active signposting” works on a recent podcast. It is dependent on creating the alternative routes for patients to follow. Training receptionists will not help, unless at the same time places are established for patients to be signposted to.

Even with the same funding some practices cope well with the level of demand, and some do not. It is not only a function of ability to recruit GPs, or the ability to signpost. I have seen a number of examples where the ratio of GP sessions to patient population is the same or higher, but the ability to cope with the workload is significantly worse. When I have looked into why this is, a key factor appears to be GP generated demand.

GP generated demand are those appointments generated by the doctor (“come back in 4 weeks”) as opposed to those initiated by the patient themselves. While CCGs are working up and down the country to cajole practices into reviewing referral rates (in his paper, Does GP growth in referral link directly to growth in inpatient demand? Dr Rod Jones shows that the answer to his own question is no, and that it leads to a perceived need for higher levels of resource than is really the case), practices might be better focussing their attention on internal GP follow up rates. Rates between individual doctors vary, but the benefits of exploring and managing that variation fall directly to the practice.

Much emphasis, rightly, in general practice is given to continuity of care. Where GPs have their own lists, and know the patients better, they can be much more confident in only bringing those patients back when they know they need to be seen. Where patients simply see the next available Doctor the likelihood of follow-up appointments is higher. So the benefits of continuity of care fall to the practice as well as to the patient.

In practices with high levels of part time working the challenge of achieving this continuity can be higher. Practices in this situation that have managed it well have introduced “buddying” systems, whereby part time GPs work to manage a list together. Practices that have not are often drowning under the weight of the demand.

Use of telephone appointments, introducing new roles, active signposting and managing variation in internal follow-up rates are all actions open to all practices to take control of their own demand. When the status quo is unsustainable, becoming the hero is the only option.

In this blog, the first of two from Buckingham GP Dr Rebecca Pryse, she takes us through the practical steps to launching a new appointments system split between Same Day and Any Day appointments. Rebecca will be back later in the spring with a second blog looking at how the change has worked.

So it’s the eve of D Day or “s-D-s Day”: the day we launch our new Same Day Service. We’ve had our final partnership “huddle” at our executive meeting last night; we’ve given the final pep talks to the various teams and here we go.

This has been months in the planning for what feels like a military operation. From the Saturday strategy partners meeting one year ago where I led a “we can’t go on like this /something has to change” discussion around our access and appointment systems; to our lead partner Greg poring over stats, models and spreadsheets at his kitchen table to come up with various proposals; to our management team and IT team testing out these proposals against appointment audits and staffing rotas.

In the middle of all this we went through our second merge, a little more “thrust upon us” than the first merge just over a year before that, making us the only practice in town serving about 30,000 patients. This used up a lot of leadership energy but gave us strength in terms of clinicians (we now have 13 partners, 3 salaried doctors and 7 nurses), staff members (we now have 80 staff), population numbers and a third town centre site to work from. This enabled us to move forward in more exciting ways to change our access system.

So we moved onwards taking a proposed appointment system model to our appointments committee. This is a multidisciplinary group of reps from clinicians, management, staff and several patients who have been meeting over the past 10-15 years since we first changed our appointments from completely open access to an advanced access system – quite novel back then. This group meets intermittently to keep an eye on our access stats and patient feedback and to make constructive suggestions for change. Most recently they helped support and test out the introduction of Patient Access to our patients. The new proposal was discussed over several meetings, tweaked and approved.

Next we took the proposal to our annual “State of the Nation” protected learning afternoon. This is an annual whole staff meeting to which we invite the PPG. The new model was presented to the whole team and this was followed by small group work for each staff group to reflect back their hopes, fears and expectations of the system with some useful and constructive suggestions.

So what model did we finally decide upon? We all agreed that there are broadly two types of access required by patients: I need to see a clinician today and it doesn’t matter who I see and I need to see MY doctor or nurse who knows me best and I can wait for this appointment. We also saw a need for signposting patients first to self-care where appropriate and then to the most appropriate clinician for their problem, which does not necessarily mean a face-to-face encounter.

From these principles we have devised an offer of same day appointments (Same Day Service or SDS) or any day appointments (Any Day Service or ADS). Each service will operate from a different site within the town centre. We have calculated the balance of appointments by looking at the statistics of how appointments are currently accessed, proposing that 60% of our appointments will be made available in the Same Day Service. We have also looked to extend the range of clinicians working from this service to ensure the patients are directed to the most appropriate clinician. This means that the SDS is manned by two GP’s called GP1 & GP2, rather reminiscent of Dr Seuss with GP3 on “special days” that we predict will be busier, one or two minor illness nurses or nurse practitioners, with a paramedic to cover acute visit requests and an HCA to provide urgent diagnostics. All our reception staff have been trained as Care Navigators and patients are being asked to give a brief outline of the problem they wish to bring with an initial question of “could this be dealt with over the telephone” being asked or self care advice given as appropriate. Our paramedic and two of our nurses have just completed the minor illness nurse-training course and two of our nurses already prescribe. We have just appointed a minor illness nurse who fulfills her dream of moving from A&E back to primary care.

In our other two sites the Any Day Service will run: the clinicians here will be offering slightly longer appointments which can be booked in advance by patients who benefit from continuity. There will still be some Same Day availability in this service and these GPs will be offering routine, pre planned visits to appropriate patients. It is planned that all urgent and same day work should be absorbed by the Same Day Service allowing the Any Day GP to plan their day more proactively and offer more complex care as needed without being rushed into 10 minute slots. They will of course keep a view of the SDS and be able to offer support if that system is becoming overloaded. We have recruited a new, additional GP who will start in September. All GPs will work some time in both systems.

In the background all our staff teams have been working hard together to ensure this new system will run smoothly and there is a general buzz of excitement in the practice as sDs-Day has approached, this in itself has felt uplifting to me particularly after they have been through a couple of years of immense change already. So we have all read the protocols and checked the process maps covering all eventualities, looked at the rotas, updated our computer screens ready for tomorrow.

Our practice manager has to be particularly congratulated, as she must be googly-eyed sorting out what has become quite a complex rota. It sounded so simple at the start but when you build in the fact that as well as seeing patients in our three sites, we also run clinics in two boarding schools and one University, we look after 4 nursing homes, we provide one GP session per day to our local community hospital and we are a training practice not only for GPs and practice nurses but for our local Medical school with 2 students in most days seeing patients……… she has politely told us to stop asking if she can sort out any more “tweaks” to her system, just for now, please. But we are keen to work in a PDSA cycle so the snag/learning list will start tomorrow as soon as the front doors open!

Dr Rebecca Pryse is a GP Partner at The Swan Practice in Buckingham. You can contact Rebecca via rebecca.pryse@nhs.net The Practice website is www.theswanpractice.co.uk

It is astonishing that despite the huge challenge the lack of GPs wanting to be partners is presenting for general practice, little if any training exists for GPs considering the step up from salaried to partner.

Taking on responsibility for a business, for its staff, for its performance, and for its liabilities, is a big commitment. While in the past GPs took it on because that was the established career route for them, that no longer appears to be the case. Increasingly GPs are opting out of being a partner, and taking on salaried, locum or portfolio careers. Even GPs who had previously become partners are now choosing these alternatives.

This reluctance by some to take on a partnership position, along with the precarious position many practices are now in, is making everyone nervous. Those considering becoming a partner have few places to go to understand exactly what is involved. Dismissing the risks on the basis that others have been able to manage them no longer feels a possibility, and a more considered examination of what is involved is required before such a big decision can be made.

It is into this environment that we are developing a training programme for GP partners. It is for those GPs who are considering becoming a partner, want to understand better what is involved, and want to develop the skills to be a good partner should they choose to make that step. It is also for those GPs who have already made the decision to become a partner, and want training and development to ensure they can be successful in the role.

The programme is in its infancy. We want to develop the programme in partnership with those who need it. Below are all the areas that we are considering including within the programme. What we would like from you is feedback on which areas you think are most important, which areas are not needed, and which areas are missing.

Section 1: Internal – understanding the business

Success Measures: What constitutes success for the practice? Is the practice there to serve patients or to make money? What does independent contractor status really mean?

Partnership: What is a partnership; why partnership agreements are important; what makes a good partnership agreement; building a strong partnership team; “last man standing” and strategies for dealing with it.

People: How to lead people, how to manage people (and understanding the difference!); dealing with difficult people (including other partners!); staff appraisals; staff surveys; team meetings; the importance of coffee.

Finances: Partner financial responsibilities; dealing with accountants; understanding cash flow; how to manage the finances.

Processes: Appointment systems: the good, the bad and the ugly; DNAs; workflow redirection; active signposting. How to implement change within the practice.

Property: Understanding premises; types of ownership of property; leases and rent reimbursement; working with NHS Property Services.

Practice Manager: What to expect from your practice manager; how to get the best out of them; understanding the difference between the role of the practice manager and the role of a GP partner; how to know if you need to change your practice manager and how to do it.

Section 2: External – understanding the environment

NHS: Understanding where GP practices fit within the NHS; the different structures and types of organisation within the NHS and how they impact on GP practices.

Commissioners: Friend or foe? Understanding the GP contract and how it works; understanding the different commissioners; how to build effective relationships with commissioners.

Regulators: The role of the CQC; surviving inspections

Other GP practices: The role of the LMC; why and how to build relationships with other GP practices; overcoming history and other barriers to joint working.

Other external relationships: Should I bother building relationships with other organisations, such as community pharmacy, community trust, local voluntary organisations, local council, local hospital? Who to prioritise; how to do it.

Section 3: Future – understanding the risks

Changing NHS: The changing NHS, including five year forward view, new models of care, STPs.

GP Forward View: What it means now and in the future; how to make the most of it.

Strategic Change: Understanding strategic options for your practice for the future; how to develop them; how to implement them.

Practice mergers: When to consider it, when not to, and how to do it successfully.

Let us know what you think. What do you think the most important training needs are for new GP partners? What would help most for someone about to take on the role? What have we missed? All your feedback greatly appreciated! Please either leave your feedback in the Comment section above or email me ben@ockham.healthcare

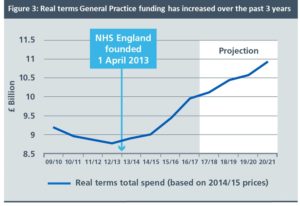

Hidden away in the latest NHS England publication[1], on page 19, is this graph (above). It is not good news for general practice.

At first glance it would seem to present a positive picture. Spending on general practice has gone up, and is planned to continue to go up until 2021. So what is the problem?

In the General Practice Forward View, published in April 2016, an additional recurrent investment of £2.4bn was promised to general practice. The parlous state of general practice was at last recognised, and (or so it seemed) that recognition was backed with real cash.

But what this graph shows is the additional investment of £2.4bn did not begin on the date of the publication of the paper. It begins around 2013, some three years earlier. A specific highlight is given to the formation of NHS England, to correlate this date with the turnaround in the funding fortunes of general practice.

The implication of this graph is that those awaiting £2.4bn of investment should really only expect less than £1bn between now and 2020/21. The graph also indicates the rate of funding increase will slow compared to the last two years. Worse, £500m of the extra money still to come has been promised for extended access, and at present most of that funding is being awarded via private tender, and not to local practices.

This should not be about headlines or political statements. It should be about properly funding a critical part of our NHS. It is no wonder that GP partners are at breaking point. According to one recent survey more than 90% of GPs have either left, have considered leaving, or have reduced their hours to be able to cope[2]. The additional funding is not a reward for general practice. It is what is necessary to keep it functioning and operating effectively at the front line of the NHS. This graph shows that not only is the funding required not going to materialise, but that the system is also going to pretend that it is.

[1] Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, March 2017