NHS England has published a number of documents recently that shed a bit more light on how the NHS architecture is changing. What are the main changes, and what are the implications of these for general practice?

The documents in question are the Strategic Commissioning Framework and the Advanced Foundation Trust Programme. They are significant because they set out a clear shift in the way the NHS is to function. In recent years we have seen a move away from the purchaser provider split, with ICBs being given the role of system integrators aiming to bring the system together to collectively decide how to make the best use of the limited resources. These documents, however, represent a shift away from this thinking.

Instead, we have a return to the purchaser provider split. The role of ICBs is now to be very clearly demarcated as that of “strategic commissioners”. Strategic commissioning, it turns out, is the updated term for what became “world class commissioning”. The document lists out the seven features or characteristics of strategic commissioning, in very much the same way world class commissioning identified 11 competencies when it was launched in 2007.

ICBs are expected to make this change quickly, “A strategic commissioning development programme will be in place from April 2026 to support ICBs and others who commission NHS services to develop as strategic commissioners. As part of this we expect ICBs to carry out a baseline assessment against this framework in March 2026 to inform the development support they need. We plan to incorporate elements of the framework in the assessment of each ICB as a strategic commissioner that NHS England is required to undertake from 2026/27.”

The difference this time round to 2007 is that ICBs are expected to do this both with far less staff and resources, and it is not the purpose for which they were originally established. How able ICBs will be to adapt and take on this new role remains to be seen, but given the inability of the NHS to produce effective commissioners in the past the odds don’t look good. This change in role may or may not be what has been behind the recent exodus of a large number of ICB leaders.

Just as ICBs are to become the new commissioners, NHS Trusts are to once again become foundation trusts, only this time they will be called “Advanced Foundation Trusts”. As in the past, NHS Trusts will be able to secure more operational and financial freedoms once they achieve this status. The main difference this time is that the role of system integrators is also effectively being shifted from ICBs to them.

Once an NHS Trust has achieved advanced foundation trust status it can take on an integrated health organisation contract, whereby it can hold the health budget for a defined local population. It will not be expected to provide all services under the scope of the contract directly, but rather will need to work with other providers (including general practice) to deliver these services.

So the new delineation is quite distinct: ICBs are to become very clearly defined as commissioners, and NHS trusts as both autonomous providers and the integrators of providers across the system. The question is where all of this leaves general practice?

The indications are that the impact could be significant. We get a strong hint of this in the Strategic Commissioning Framework, which states that,

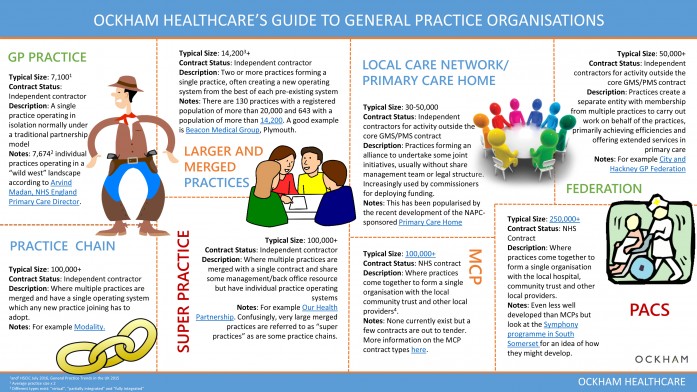

“The 10 Year Health Plan sets out a new provider system architecture for neighbourhood health. This – for the first time since the creation of the purchaser–provider split in 1991 – has the potential to shift the majority of NHS provision from a ‘receive and treat’ model to a population-based model. Individual GP practices, single neighbourhood providers (SNPs) and multi-neighbourhood providers (MNPs) are all population-based entities.” (5.2)

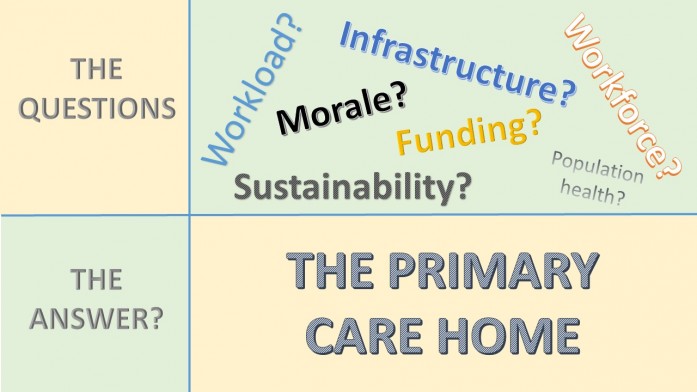

ICBs are exhorted to “shape the development of providers and use of novel contract models to create the right provider landscape to deliver population health improvement”. It very much seems as though the main lever that will be used to influence general practice will be the new neighbourhood contracts.

This was reinforced by Wes Streeting who suggested that these new contracts would be the tool to enact a “fundamental modernisation” of general practice in his speech to NHS Providers on 12th November,

“But the bright future that general practice deserves will only come through fundamental modernisation. That’s why we’re introducing two new neighbourhood contracts. A single neighbourhood provider contract for the delivery of enhanced services, for patients, through expert, multi-disciplinary teams and a multi-neighbourhood provider contract to lead the Neighbourhood Health Service at scale.”

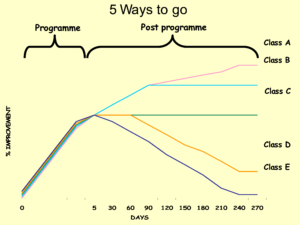

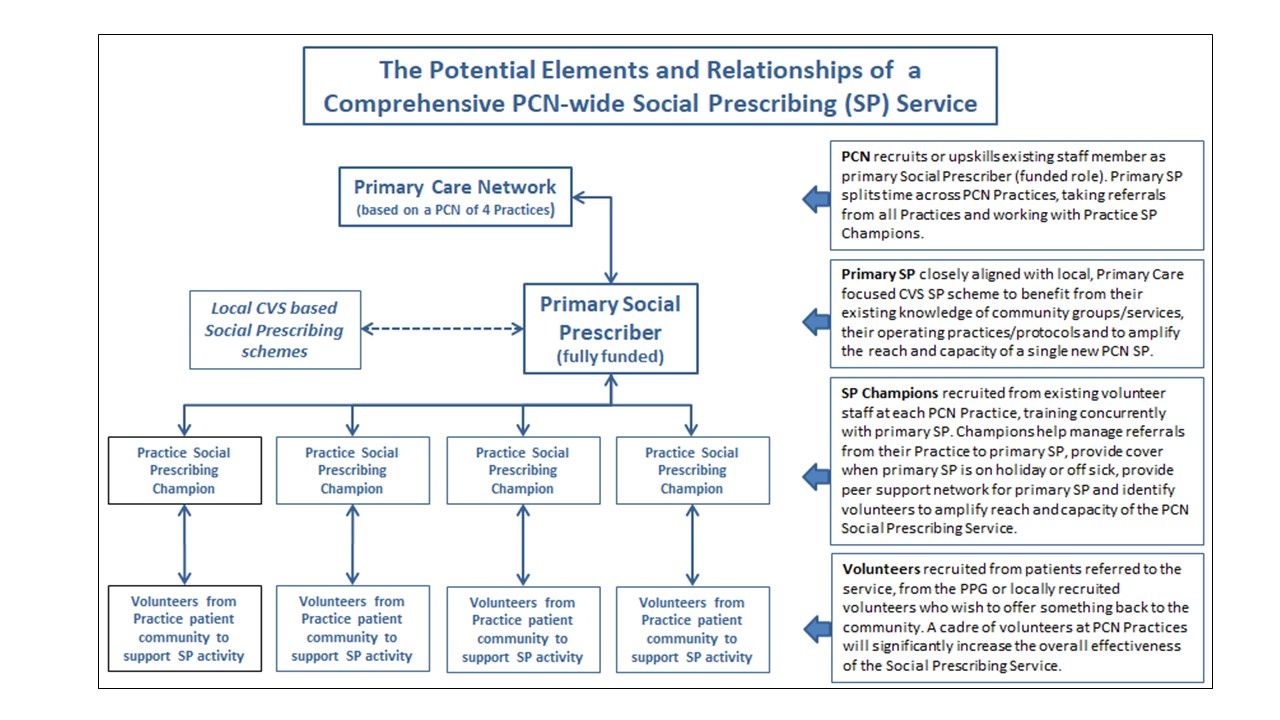

This appears to suggest that enhanced services may be commissioned in future via the single neighbourhood contract, a concern that GPC Chair Katie Bramall-Stainer also raised at the recent LMC conference. If this ends up being the case practices will get tied into neighbourhoods in very much the same way as they have with PCNs, as being without the enhanced service funding will be simply unaffordable.

According to the Strategic Commissioning Framework, “Primary care leaders are working with their ICBs to explore how best to organise their work, including through horizontal and vertical integration with other parts of the NHS, so that patients receive the appropriate care, whether episodic or ongoing co-ordinated care or part of a wider pathway of care. They are also playing a leading role in the development of neighbourhood health.” (5.1). In reality I suspect very few primary care leaders on the ground are looking to horizontal and vertical integration, but it seems likely that this is the agenda at a national level. All three of the new contracts (single neighbourhood, multi neighbourhood and integrated health organisation) may well end up pushing general practice in this direction.

This makes the guidance (promised in November in the medium term planning framework) on these new contracts extremely important indeed for general practice. The NHS is changing rapidly, and general practice will need to work hard to establish its place and maintain its independence in this new architecture.